Roads and Canals a New Style of Art 1800s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Water-Flow-Goerge-Catlin-Niagara-Falls-631.jpg)

At the outset of the 19th century, the United States was nonetheless a place where many people ate what they grew and many women fabricated the family clothes. But with technological innovations such as the railroad, telegraph and steamboat, the The states grew into one of the world's leading industrial powers. Meanwhile, the country had become a transcontinental empire, which these innovations in transportation and communications helped facilitate.

The Not bad American Hall of Wonders, an exhibition at the Smithsonian American Fine art Museum in Washington, D.C., presents a graphic representation of this transformative era. Information technology emphasizes precisely those forces of science and technology that were driving the changes: images of water, like those on the following pages, typify the interrelationships among art, engineering science and science forged past the Americans of that era. The exhibition's organizer, Claire Perry, an independent curator, writes that she was interested in "the nineteenth century'southward spirit of inquiry through science and technology, the arts, and materials of everyday life that defined the experimentations taking place in the vast laboratory of the United States."

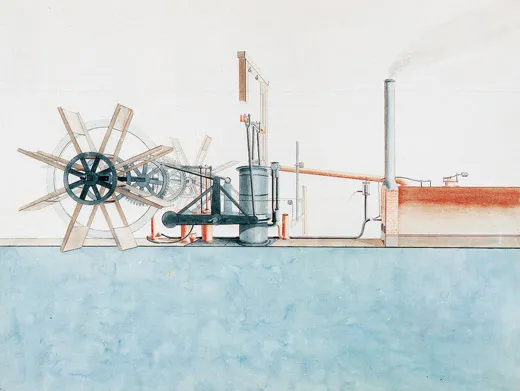

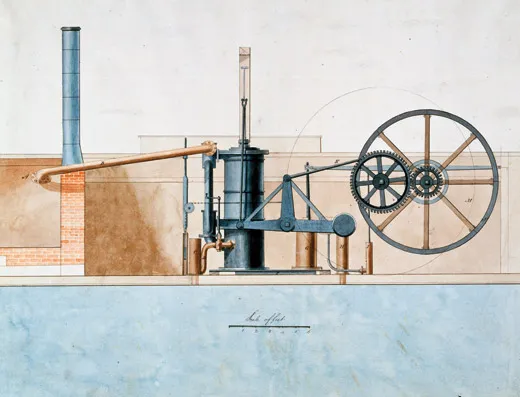

Waters were the interstate highways of the early 19th-century United States. Many Americans earned their living as farmers, and waterways provided an efficient means of getting crops to market place. The steamboat profoundly enhanced that ability. In 1787, John Fitch and James Rumsey each built American steamboats, merely they could not sustain fiscal backing and died in frustration. The first commercially successful steamboat, Robert Fulton's Clermont, plied the Hudson River starting in 1807. (The exhibition includes ii drawings, beneath right, for Fulton'southward steamboat-engine patent awarding.) Steamboats proved most valuable for trips upstream on rivers with powerful currents, of which the Mississippi was the ultimate example. Previously, traffic on the Mississippi had been generally downstream; at New Orleans boatmen broke up their barges to sell for lumber and walked back home to Kentucky or Tennessee along the Natchez Trace.

Sandbars and other obstructions impeded commerce. Abraham Lincoln was among the political leaders of the time who favored government aid for making rivers navigable. Lincoln even patented an invention to help grounded steamboats lift themselves off shoals.

Information technology was besides an era of awe-inspiring canal-building, commonly to connect two natural waterways or parallel a unmarried stream and avoid waterfalls, rapids or other impasses. The country's most economically of import and financially successful bogus waterway was the Erie Culvert in New York. Astonishingly, this ambitious undertaking from Albany to Buffalo—363 miles—was completed in eight years. The culvert contributed mightily to the prosperity of New York City and brought commercial civilisation to the western role of the land, including Niagara Falls.

George Catlin's eye-popping, circa 1827 painting A Bird'south Eye View of Niagara Falls synthesizes landscape art with cartography. The bird'south-eye view that we take for granted today likely struck viewers at the time as highly imaginative. Niagara Falls, which Perry describes equally "an icon of the beauty, monumentality and ability of the U.S. landscape," typified for many Americans the tremendous power of Nature and God. Meanwhile, businessmen harnessed Niagara's ability for industry.

Catlin, broken-hearted to record an America in the procedure of disappearing, created Buffalo Herds Crossing the Upper Missouri in 1832. The painting contrasts the vast number of bison swimming beyond the river with the handful of explorers in a rowboat. A human in the boat seems to wave his burglarize defiantly at the animals, a gesture that to a modern viewer would appear to predict their coming slaughter.

For 19th-century Americans, water represented both nature and civilization. The painter Robert South. Duncanson, then the nation'southward well-nigh celebrated African-American creative person, subtly addresses both these themes in Landscape with Rainbow of 1859. The rainbow, of course, has been the object of scientific, creative and religious involvement for centuries. And this painting has been described over the decades as an Idealized celebration. The creative person captures the transition from wilderness to settlement. The at-home h2o and verdant land are balanced by the children, the cabin and the cattle grazing. The rainbow—one of nature'southward near evanescent phenomena—reminds u.s.a. today that it was also a delicate moment. The work is a rich and, to our eyes, poignant commentary on Americans' early enthusiasm for progress.

Daniel Walker Howe is a historian and the writer of What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848.

0 Response to "Roads and Canals a New Style of Art 1800s"

Post a Comment